Amama Asif, Mounia Khalil, Alan Rozenblit, Tayler Williams

Department of Biology, Rutgers University, Camden NJ 08102

Abstract

Pan-neuronal knockdown of Ca-α1T, a T-type calcium channel in Drosophila melanogaster, increases sleep. However, researchers do not know which specific neuronal circuit is responsible for this effect. Circadian pacemaker neurons (CPNs) are one of many cell types that contain this T-type calcium channel, and these neurons take part in establishing normal circadian behaviors. We identified certain CPNs as possible candidates in narrowing down which neuronal circuit is responsible for the increase in sleep. We hypothesize that the knockdown of Ca-α1T in these certain CPNs will cause an increase in sleep, with an increase more pronounced in tim-expressing CPNs. To test this hypothesis, we utilized the GAL4-UAS system to target specific CPNs with RNA interference of Ca-α1T. An ethoscope, a computer-mediated apparatus, was paired with rethomics, a set of R packages, to track and analyze the activity of Drosophila through their movement. The data demonstrates that the tim-CaRrnai and pdf-CaRrnai lines exhibit less activity when compared to the tim-GAL4 line. However, no significant difference in sleep exists between the experimental and control groups. Thus, our experiment suggests that the knockdown of Ca-α1T in tim– and pdf-expressing CPNs does not have a significant effect on sleep.

Introduction

Sleep is critical to the survival of all animals due to its importance in the central nervous system, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and metabolic health (Ramar et al., 2021). Still, there are many unanswered questions surrounding the topic of sleep and how anomalies in its mechanisms lead to disorders, such as narcolepsy, idiopathic insomnia, and restless legs syndrome, among others (Abad and Guilleminault, 2003). Scientists are particularly interested in exploring neuronal processes that allow an organism to sleep. In this study, we aimed to investigate a type of transmembrane protein that appears to influence the facilitation of sleep: T-type calcium channels; more specifically those located in the circadian pacemaker neurons (CPNs) in Drosophila melanogaster. The study of sleep mechanisms allows for both the identification and exploration of possible treatments for sleep disorders.

Calcium channels are categorized as a type of ion channel, a transmembrane protein that allows for permeability to specific ions. Ion channels are divided into three categories based on their regulation: ligand-gated, voltage-gated, or both. Voltage-gated channels, such as T-type channels, are regulated by the depolarization of membranes. This depolarization allows for the influx of calcium into the cell which, depending on the cell type, can have various functions in the body (Cooper, D. 2023). Three different genes in mammals encode the pore-forming alpha subunits of T-type channels, Cav3.1, 3.2, and 3.3. Both Cav3.1 and 3.3 are highly expressed in the thalamus, where oscillations required for NREM sleep are generated (Jeong et al., 2015). Both reduced delta-wave activity and sleep stability have been observed in mice lacking Cav3.1, suggesting that mammalian T-type currents have a sleep-promoting effect. In contrast to mammals, Drosophila melanogaster only has one T-type calcium channel, Ca-α1T. In Drosophila lacking this channel, it was revealed that motor neurons exhibit reduced low-voltage-activated calcium currents, as well as reduced high-voltage-activated calcium currents. This finding suggests that Ca-α1T may possess interesting biophysical properties as a T-type channel(Jeong et al., 2015). Ca-α1T is observed to have a significant effect on rhythmicity and is believed to influence the firing of circadian clock related neurons downstream of the core circadian clock (Jeong et al., 2015). Their effect on pacemaker activity, relation to sleep, and widespread distribution are principal reasons to explore this specific channel.

A study identified many similarities of Ca-α1T to rat T-type channel Cav3.1 (Jeong et al., 2015). Using voltage-clamp analysis on Xenopus oocytes and HEK-293 cells expressing the two channels, it was found that Ca-α1T’s properties align with a typical T-type calcium channel. Through immunohistochemistry, Ca-α1T was tagged with GFP to visualize its expression pattern in the adult brain. The channel was found to display a broad expression pattern. The study also found that female Drosophila lacking the Ca-ɑ1T channel slept more than controls. This difference in behavior was most prominent when comparing individuals kept in constant darkness. This discovery suggests that Ca-ɑ1T may promote wakefulness rather than sleep stability. The circadian rhythms of Ca-α1T-null mutants were not affected by the knockdown of Ca-α1T. These findings contradicted the previously held notion that T-type calcium channels promote sleep stability. Many neuronal GAL4 drivers known to cover sleep centers were used to knockdown Ca-α1T to specify which brain region or circuit is associated with regulating sleep; however, none of the drivers used were able to significantly alter sleep (Jeong et al., 2015).

Circadian pacemaker neurons exhibit daily rhythms in intracellular calcium levels that are required for establishing normal circadian behaviors. These levels are partially sourced from extracellular calcium regulated by Ca-α1T (Liang et al., 2022). A study conducted by Liang et al. is one of many that identified the five major pacemaker groups: the small and large ventral lateral neurons (s-LNv and l-LNv), dorsal lateral neurons (LNd), and groups #1 and #3 dorsal neurons (DN1 and DN3). Given that sleep is regulated by circadian and homeostatic processes (Cirelli and Bushey, 2008), knockdown of Ca-α1T in a specific neuronal subpopulation within CPNs has the possibility of playing a key role in sleep. It was shown that when T-type calcium channels were deactivated in CPNs that express pigment dispersing factor neuropeptide (PDF), s-LNv and l-LNv, as well as in CPNs expressing the clock gene timeless (tim), all five groups, circadian behavioral arrhythmicity was observed and calcium circadian rhythms in most CPNs were also affected (Liang et al., 2022). Jeonget al.’s study targeted various neuronal subpopulations, including s-LNv and l-LNv, and found inconclusive results; however, they did not target the wider range of tim-expressing CPNs. By exploring the effects of targeting this wider range of CPNs on sleep, a more nuanced understanding of the functional roles of Ca-α1T may be uncovered. By knocking down Ca-α1T expression exclusively within CPNs via RNAi-mediated inhibition, we aim to discern the specific contributions of this calcium channel to sleep regulation. This research can shed light on key questions regarding the physiology of T-type calcium channels and the mechanisms that underly sleep, allowing for the development of therapeutic strategies.

Materials & Methods

Drosophila Stocks

Drosophila lines tim-GAL4(#29233), pdf-GAL4(#6899), and UAS-JF02150-RNAi (#26251) were ordered from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Drosophila from each of the three stocks were selected to be used as the background control groups. To produce mutant Drosophila with Ca-α1T knockdown in CPNs, we bred tim-GAL4males with virgin UAS-JF02150-RNAi females to allow for Ca-α1T knockdown in all CPNs in offspring labeled as tim-CaRrnai. Pdf-GAL4males were bred with virgin UAS-JF02150-RNAi females to allow for Ca-α1T knockdown in only s-LNv and l-LNv in offspring labeled as pdf-CaRrnai. tim-CaRrnai and pdf-CaRrnai were used as experimental groups. All groups were reared on a standard cornmeal diet at room temperature.

The offspring is characterized by the expression of the GAL4 transcriptional activator protein under the control of the respective GAL4 line, and the insertion of the UAS-JF02150-RNAi transgene directly ahead of the gene encoding for Ca-α1T siRNA. The siRNA marks Ca-α1T mRNA for degradation prior to translation, consequently the Ca-α1T protein is not produced. This occurs only if both the GAL4 protein and the UAS sequence are present in a particular cell type. The cross between pdf-GAL4 and UAS-JF02150-RNAi consequently knocks down Ca-α1T production exclusively in s-LNvs and l-LNvs in the offspring. The tim-GAL4 and UAS-JF02150-RNAi cross knocks down Ca-α1T production in all five noted CPNs. The resulting GAL4-UAS progeny thereby provides a model system to study the functional roles of Ca-α1T in these specific neuronal subtypes.

Sleep Analysis

The ethoscope system was used to analyze sleep in experimental and control groups. The ethoscope is composed of a 3D-printed arena and a 3D-printed chassis (Geissmann et al., 2017). The arena is designed to hold a maximum of twenty tubes, each containing one Drosophila. Each tube also contained yarn, a plastic cap, and a standard cornmeal diet as a food supply. The chassis holds a rPi (raspberry pi computer) and its associated rPi camera to measure and store activity levels of each Drosophila. The computer assigns a number to represent the activity level of a specific Drosophila per minute. A value of zero represents no activity. Any positive integer represents activity; larger integers indicate more activity occurred during that minute. Data from the ethoscope is provided in arbitrary units of activity per minute. The commonly accepted criteria that define sleep in Drosophila include behavioral quiescence (immobility) and a reversible increase in arousal threshold. Drosophila that experienced periods of immobility lasting for five minutes or longer rarely showed a motor response to stimuli. This is in contrast to those who were mobile right before a stimulus was applied, who readily responded to low and medium stimulus intensities. Essentially, sleep has been widely defined as a period of five minutes or more of behavioral quiescence (Cirelli and Bushey, 2008). This definition of sleep is also used by the ethoscope when determining whether Drosophila are awake or asleep. The activity of each Drosophila was measured for 48 hours at room temperature with natural light exposure through windows.

Statistical Analysis

Using the data generated by the ethoscope, we averaged the activity of every Drosophila to generate an average activity level per minute for each genotype. This served as our preliminary analysis. Data was analyzed via the R-based rethomics package (Geissmann et al., 2019) that is designed to be used with the ethoscope data. This code uses the activity data previously described to measure the amount of time slept at night, time slept during the day, and time spent sleeping overall. Sleep profiles for the experimental groups were also generated. The rethomics based analysis is more precise than our preliminary analysis and therefore our discussion is more heavily based on these results.

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to determine if significant differences between experimental groups exist, and whether these differences exist at the genotype level and/or sex level. The data was then binned based on time of day and plotted separately to reveal if any differences existed between night and day sleep. Sleep profiles (in Zeitgeber time scale) were generated to visualize circadian rhythms of experimental groups, allowing us to see where peak and minimum levels of activity occur. Each of the experimental groups was represented by a different line across the same time scale. All figures and statistical analyses were produced using the R-based rethomics package.

Results

Tim-GAL4 line exhibits the highest level of activity compared to other lines

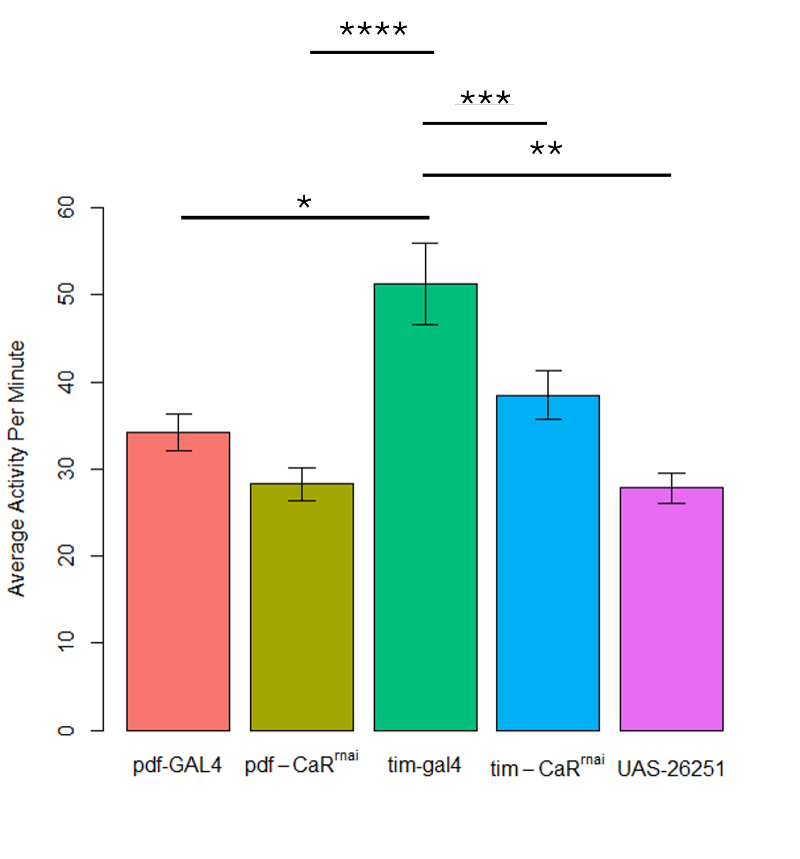

Our initial analysis of the control groups (pdf-GAL4, tim-GAL4, and UAS-JF02150-RNAi) revealed a significant difference between tim-GAL4 & pdf-GAL4 (p = <0.001) and between tim-GAL4 & UAS-JF02150-RNAi (p = <0.001) (Figure 1). No significant difference existed when comparing UAS-JF02150-RNAi & pdf-GAL4 (p = 0.45). Post-hoc Tukey test revealed that pdf-GAL4 had less activity than tim-GAL4, suggesting that pdf-gal4 had more overall sleep (p = 0.004) (Figure 1). Since the one-way ANOVA comparing tim-GAL4 line & UAS-JF02150-RNAi, and pdf-GAL4 & UAS-JF02150-RNAi indicated significant differences between the control groups in all but one comparison (pdf-GAL4 vs UAS-JF02150-RNAi), the control groups were kept separate during the data analysis procedure. A one-way ANOVA analyzing activity levels between the five groups followed by a Tukey post-hoc test revealed significant differences in activity levels between the tim-CaRrnai(38.5 ± 2.8 a.u.) and tim-GAL4 line (51.3 ± 4.7 a.u.) (p = 0.009), and pdf-CaRrnai (28.2 ± 1.9 a.u.)and tim-GAL4 line (p = <0.001). However, no significant difference in activity levels exists between the pdf–CaRrnai line and tim-CaRrnai line (p = 0.1), pdf–CaRrnai line and pdf-GAL4 line (p = 0.6), tim-CaRrnai and the pdf-GAL4 genotype (34.2 ± 2.1 a.u.) (p = 0.8), or pdf-GAL4 and UAS-JF02150-RNAi genotype (27.8 ± 1.8 a.u.) (p = 0.45).

Figure 1: Activity in Experimental Groups. Comparison of average activity level per minute between genotypes: pdf-CaRrnai (n = 21), tim-CaRrnai (n = 29), tim-GAL4 (n = 24), pdf-GAL4 (n = 22), and UAS-26251 (n = 38). Data plotted as mean ± sem.

No differences in sleep among GAL4 lines, UAS-JF02150-RNAi, and GAL4 x UAS crosses

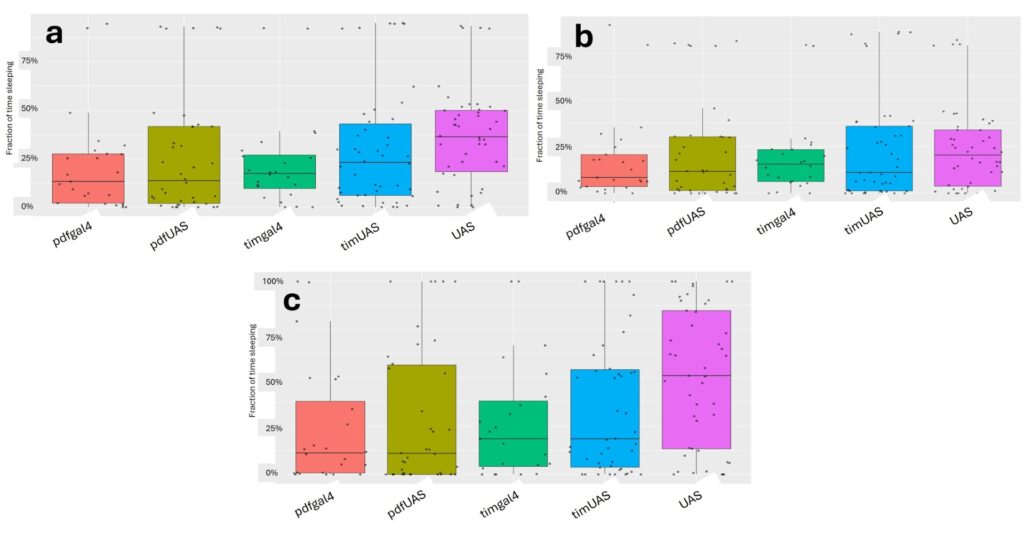

Using the R-studio based rethomics package described previously, an analysis of sleep was conducted. No significant differences existed when comparing any two genotypes. The median fractions of time spent sleeping during a 24-hour period are similar for each genotype (Figure 2a). There is an observed increase in the median percentage of time spent sleeping during nighttime (Figure 2c) in comparison to daytime (Figure 2b), reflecting the diurnal behavior of Drosophila melanogaster. This difference is most profound in the UAS-JF02150-RNAi genotype.

Figure 2: Fraction of Time Spent Sleeping. (a) Representation of the fraction of time spent sleeping during a 24-hour period. (b) Representation of time spent sleeping during daytime (ZT0 [ ̴ 6:35 AM] to ZT12 [ ̴ 6:35 PM]). (c) Representation of fraction of time spent sleeping during nighttime (ZT12 [ ̴ 6:35 PM] to ZT0 [ ̴ 6:35 AM]).

Figure 3: Fraction of Time Spent Sleeping, Separated by Sex. (a) Comparison of the fraction of time males (bottom) and females (top) spent sleeping during a 24-hour period. (b) Comparison of the fraction of time males (bottom) and females (top) spent sleeping during daytime (ZT0 [ ̴ 6:35 AM] to ZT12 [ ̴ 6:35 PM] ). (c) Comparison of the fraction of time males (bottom) and females (top) spent sleeping during nighttime (ZT12 [ ̴ 6:35 PM] to ZT0 [ ̴ 6:35 AM]).

Figure 4: Fraction of Time Spent Sleeping During Daylight and Nighttime Hours: Ethogram consisting of the sleep profiles of each genotype, reflecting any possible deviations from the normal diurnal clock of Drosophila.

Discussion

In this study, we knocked down the Drosophila T-type calcium channel, Ca-α1T, in two neuronal sub populations of CPNs based on gene expression. When comparing the amount of activity exhibited by each genotype, we found that knockdown of Ca-ɑ1T had an impact on activity levels (Figure 1). When analyzing the amount of time each genotype spent sleeping, we found that knockdown of Ca-ɑ1T did not produce significant differences in sleep between genotypes over a 24-hour period (Figure 2a). There were no significant differences found when breaking up the 24-hour period into 12 hours of daytime and 12 hours of nighttime (Figures 2b and 2c). Further, we observed whether a significant difference in time spent sleeping could be observed by looking only at males or females. We found that neither knockdown males nor knockdown females slept significantly more when compared to males or females from the control groups over a 24-hour period (Figure 3a). There were no significant differences found when breaking up the 24-hour period into 12 hours of daytime and 12 hours of nighttime (Figures 3b and 3c). We found significant differences in activity between our control groups: tim-GAL4, pdf-GAL4, and UAS-JF02150-RNAi. Although these genotypes only differ by the insertion of either a GAL4 line or UAS line, there were measurable differences in activity when comparing the groups. A one-way ANOVA revealed that UAS-JF02150-RNAi and pdf-GAL4 line were not significantly different from one another, yet both groups were significantly lower than tim-GAL4. These findings contradict the assumption that all control groups would sleep similarly. This phenomenon was also observed in a previous study where in daytime conditions one of the control groups, Ca-ɑ1T rescue, slept more in light-dark conditions than the other control group, w118 (Jeong et al., 2015). We believe that the observed differences may be attributed to using homozygous progeny as experimental units. Although all Drosophila in a particular genotype were subjected to the same conditions, we observed a minority of Drosophila within each genotype that exhibited altered phenotypic traits when compared to the rest, such as skinnier midsections and thinner banding, despite never mating with a different genotype. It is possible that the presence of two UAS lines or two GAL4 lines via the mating of two wild-type Drosophila has the ability to produce mutant homozygous individuals with phenotypic and behavioral differences not previously discovered.

The GAL4-UAS system is designed to target a specific cellular target to express a specific gene of interest. Despite being a common method to knock down a gene, the presence of both a GAL4 line and UAS line does not ensure that the protein, in this case Ca-α1T, is sufficiently knocked down. Some GAL4 lines are simply not efficient due to them expressing low levels of GAL4 compared to other GAL4 lines (Heigwer et al., 2018). Since we did not verify the knockdown sufficiency, it is possible that some or even all the Drosophila within these experimental groups still had some level of Ca-α1T production in their respective tim– or pdf- expressing CPNs. Consequently, the pdf-CaRrnai and tim-CaRrnai lines may have insufficient knockdowns, and do not reflect the true behavior of Drosophila experiencing knockdown in Ca-ɑ1T expression. Future studies could look at the efficiency of Ca-α1T knockdown via western blot or immunohistochemistry to determine whether sufficient knockdown of the protein took place. An additional caveat is the possibility of genetic recombination. For this experiment we operated under the assumption that recombination did not happen, and each Drosophila of the F1 generation received the respective GAL4 and UAS lines. It is possible, however, that genetic recombination prevented either the sperm, egg, or both from having the GAL4/UAS sequences in their genetic sequence. As a result, the joining of this egg and sperm leads to an F1 generation that does not have both the GAL4 line and UAS line in its genetic sequence, leading to no RNAi production, no Ca-α1T knockdown, and consequently sleep behavior that resembles that of the background control groups.

The sleep analysis shows no significant differences amongst the groups studied besides activity levels, and the lack of significant differences is contributed by variability present in the data. The variability in the data may result from the methods and materials used, as Jeong et al. subjected Drosophila to one day of habituation in an incubator, followed by four days of recording sleep data (two days of 12hr:12hr light-dark conditions and two days of continuous darkness). We believe that utilizing an incubator in the same way during future trials allows for a better controlled environment by ensuring a constant temperature throughout the span of the experiment, as GAL4 activity is affected by temperature (Duffy, J. B. 2002). Differences in temperature, and thus GAL4 activity, across several trials of data collection can misrepresent the effects of Ca-α1T knockdown in these neuronal subpopulations discussed. Additionally, future trials should include the 24 hour habituation period ahead of data collection, and two to four days of continuous darkness after the original 48 hours of light-dark conditions to observe any significant differences. The increase in total sleep observed because of Ca-α1T knockdown has been particularly most prominent during the subjective day under constant darkness (Jeong et al., 2015), so collecting and analyzing data using the same methods and materials may provide more conclusive results.

Conclusions

Despite the analysis of activity levels indicating significance, we conclude that knocking down Ca-ɑ1t in both pdf-expressing and tim-expressing neurons does not lead to an increase in sleep. Consequently, knockdown in tim-expressing neurons does not lead to a larger increase in sleep than knockdown in pdf-expressing neurons does. Many different factors could be contributing to the results: errors in the RNAi mechanism, errors during the breeding process and collection of GAL4-UAS positive Drosophila, and a lack of experimental evidence of the extent of RNAi knockdown in both tim-CaRrnai and pdf-CaRrnai genotypes. The large variability in the data suggests that a more controlled environment is necessary to form definitive conclusions. If the hypothesis is not supported, we plan to explore whether a different subpopulation of neurons is responsible for the increase in sleep observed when knocking down Ca-ɑ1t pan-neuronally (Jeong et al., 2015), or if the increase in sleep can only be observed when pan-neuronal knockdown takes place. We conclude that Ca-ɑ1t knockdown does not impact sleep, and no observable increase of sleep is seen when comparing knockdown of Ca-ɑ1T in tim-expressing CPNs to knockdown of Ca-ɑ1T in pdf-expressing CPNs.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our utmost gratitude to Dr. Nathan Fried for his helpful advice and overall support on this project. We also want to thank systems administrator Jim Schmincke from Rutgers Camden IT for assisting in the setup of the ethoscope software and running the ethoscope apparatus. We thank the Biology Department of Rutgers University – Camden for providing lab resources and funding.

References

Abad VC, Guilleminault C (2003) Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders: a brief review for clinicians. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 5:371–388.

Cirelli C, Bushey D (2008) Sleep and wakefulness in Drosophila melanogaster. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1129:323–329.

Cooper, D. (2023). Biochemistry, calcium channels. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562198/

Geissmann Q, Garcia Rodriguez L, Beckwith EJ, French AS, Jamasb AR, Gilestro GF (2017) Ethoscopes: An open platform for high-throughput ethomics. PLoS Biol 15:e2003026.

Geissmann Q, Rodriguez LG, Beckwith EJ, Gilestro GF (2019) Rethomics: An R framework to analyse high-throughput behavioural data. PLOS ONE 14:e0209331.

Halpern, M. E., Rhee, J., Goll, M. G., Akitake, C. M., Parsons, M., & Leach, S. D. (2008). Gal4/UAS transgenic tools and their application to zebrafish. Zebrafish, 5(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1089/zeb.2008.0530

Heigwer, F., Port, F., & Boutros, M. (2018). RNA interference (rnai) screening in drosophila. Genetics, 208(3), 853–874. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300077

Jeong K, Lee S, Seo H, Oh Y, Jang D, Choe J, Kim D, Lee J-H, Jones WD (2015) Ca-α1T, a fly T-type Ca2+ channel, negatively modulates sleep. Sci Rep 5:17893.

Liang X, Holy TE, Taghert PH (2022) Circadian pacemaker neurons display cophasic rhythms in basal calcium level and in fast calcium fluctuations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 119:e2109969119.

Ramar K, Malhotra RK, Carden KA, Martin JL, Abbasi -Feinberg Fariha, Aurora RN, Kapur VK, Olson EJ, Rosen CL, Rowley JA, Shelgikar AV, Trotti LM (2021) Sleep is essential to health: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med 17:2115–2119.